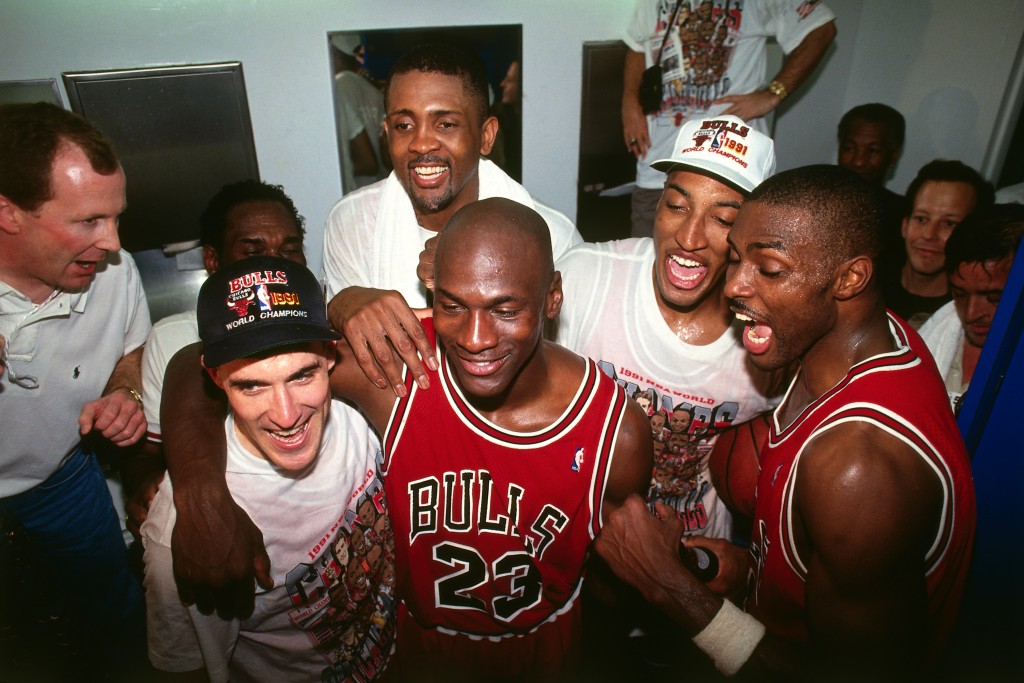

We’re just moments away from the highly anticipated release of “The Last Dance,” Set to premier Michael Jordan and the infamous 1997/98 Bulls team, it’ll give fans a never-before-seen glimpse into the world of basketball’s greatest team.

But all of this begs the question: how was all of this even possible? According to what was told to ESPN, a lot of planning.

Silver believed in NBAE’s mission as the league’s archivist, and in opening up the game and its personalities to the world. That meant more than postgame interviews and home videos of championship runs. To do something more, he would have to convince the best team in the league and the best player in the league to let cameras into their inner sanctum.

He started by asking Bulls owner Jerry Reinsdorf, who was open to the idea, but only if Jordan and Jackson were on board.

“The coach, at the end of the day, controls the locker room,” Silver said. “So we needed Phil’s cooperation.”

You can actually see Silver meeting with Jackson on the steps of the Bulls team hotel in Paris, in Episode 1 of “The Last Dance,” the 10-part documentary on the 1997-98 Bulls, which begins airing on ESPN at 9 p.m. ET Sunday and continues for the next five weeks.

Convincing Jordan wasn’t as easy.

“Our agreement will be that neither one of us can use this footage without the other’s permission,” Silver told Jordan. “It will be kept — I mean literally it was physical film — as a separate part of our Secaucus [New Jersey] library. Our producers won’t have access to it. It will only be used with your permission.”

Now that was something.

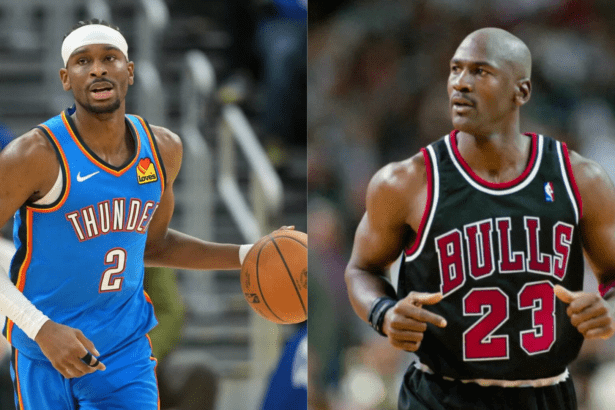

Jordan had successfully controlled his likeness since he came into the league in 1984. He was one of two players (fellow David Falk client Patrick Ewing was the other) who opted out of the players’ union’s group licensing program, figuring correctly they’d make exponentially more by doing their own marketing deals.

When he’d sue to enforce that deal, Falk’s argument was that the value of Jordan’s image became diluted each time it was used. But if Silver was willing to front all of the production costs and give Jordan control over the content, there wasn’t much downside.

“Worst-case scenario,” Silver told Jordan, “you’ll have the greatest set of home movies for your kids ever created.”

It was a brilliant pitch, and maybe the only one Jordan would have agreed to. When Jordan hit the winning shot in the 1998 NBA Finals to clinch the Bulls’ sixth NBA title and second three-peat, Thompson felt he had just shot one of the most incredible sports documentaries ever.

After years of waiting, the documentary sat, collecting dust in Secaucus. Different faces over different years tried to make the pitch to Jordan, but none ever went so far as to get a face-to-face meeting.

It wasn’t until years later that the project finally took the breath of life.

In February 2016, he saw an opening.

“The O.J. [Simpson] documentary had just premiered at Sundance the previous month at eight episodes and like 450 minutes,” Tollin said. “[‘Making a Murderer’] had just premiered on Netflix at 10 episodes. … People were now consuming longform documentaries, multipart documentaries.

“As a guy who’s done documentaries since the ’70s, less was always more. And now all of a sudden, more is more.”

He arranged a meeting with Polk and Estee Portnoy, two of Jordan’s most trusted business associates, to make his pitch. Over the next few months, the conversations continued. Tollin sketched out a proposal of what an eight-episode series might look like. Finally, in June 2016, a meeting was set with Jordan, now owner of the Charlotte Hornets.

Producer Mike Tollin had the meeting with Jordan, where he was finally able to close the deal.

He headed over to Jordan’s office at the Hornets’ arena, hoping he would get a chance to present the lookbook he had made. No one had ever gotten this close before. But Portnoy and Polk could only open the door. Tollin had to close Jordan.

“The first page was a letter that I’d written to him,” Tollin said. “Dear Michael, every day kids come into my office wearing your shoes, who’ve never seen you play.

“It’s time.”

Tollin could tell Jordan was engaged, because he stopped for a moment to put on his reading glasses.

Jordan read every page. He looked at the pictures. He read the quotes. Then he smiled as he looked at the eight episode thumbnail sketches.

The last page of the presentation was a look at the documentaries, movies and shows Tollin and his company, Mandalay Sports Media, had done.

“So there’s Kareem [Abdul-Jabbar], there’s Hank Aaron, there’s ‘Varsity Blues,’ there’s ‘Coach Carter’ and so forth,” Tollin said. “He’s actually looking at them all, and in the bottom right corner is ‘Iverson.’ He goes, ‘You did that?'”

Tollin mumbled a cautious, “Yes.”

Jordan took his glasses off, looked up and said, “I watched that thing three times. Made me cry. Love that little guy.”

Then he walked around the desk, extended his hand and said, “Let’s do it.”

After more years of production, the documentary was finally ready, and in a few hours, it will be delivered to the whole world to see.

The journey we’ll get to see on camera will be epic and legendary. But the journey that got the film to the big screen may have been the hardest bit of all.