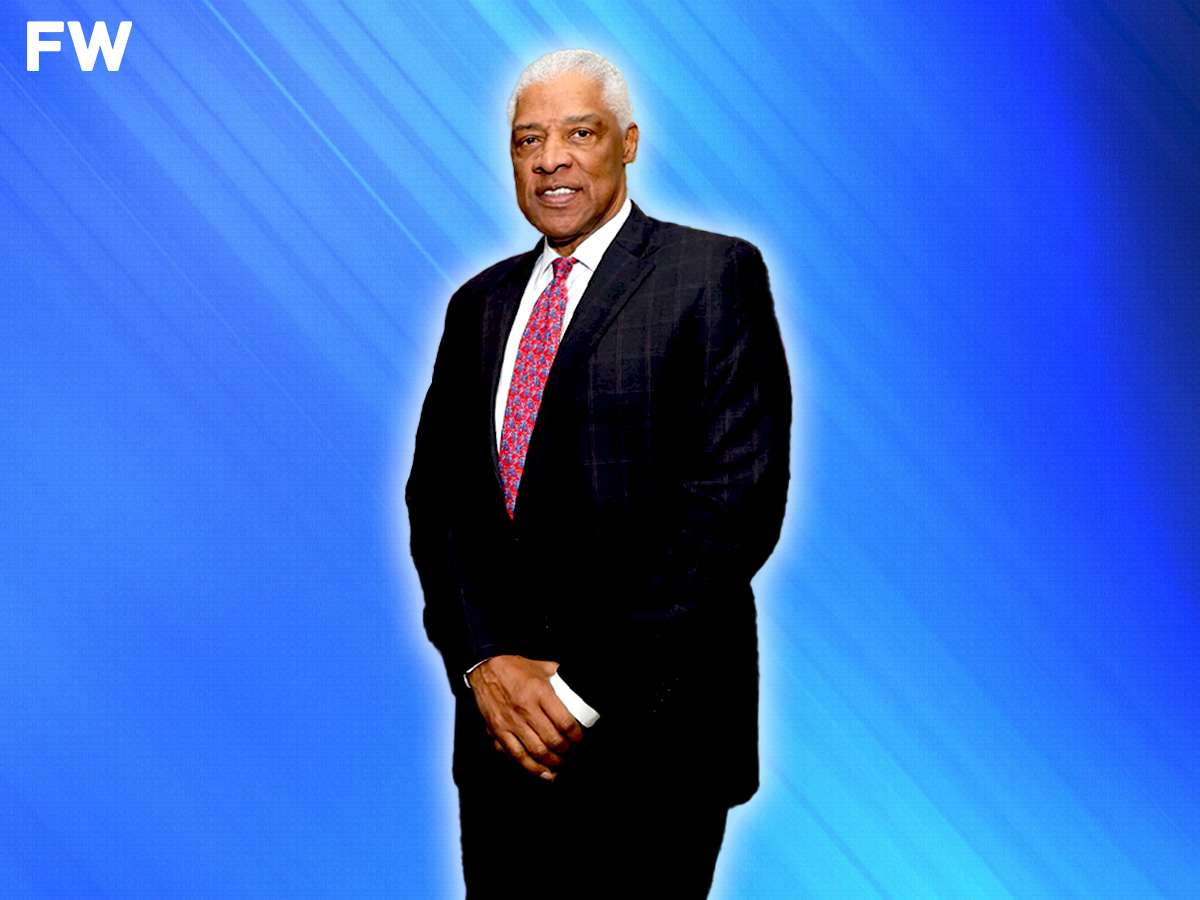

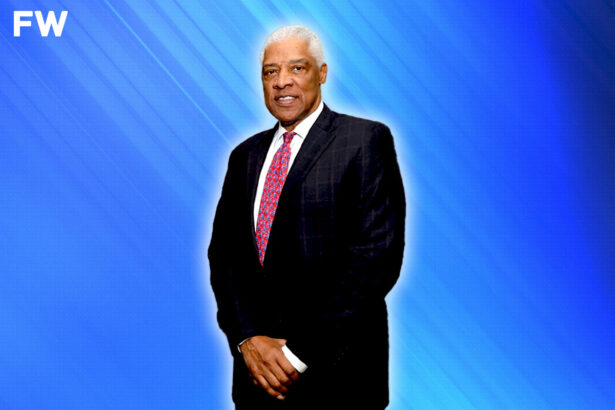

Julius Erving does not criticize modern players out of bitterness. When he talks about load management, he frames it as a reflection of how different the league has become. In his era, sitting out healthy simply was not an option. Not because players were superhuman, but because their jobs were never fully secure.

On the Million Dollaz Worth Of Game podcast, Erving said:

“I think there was great insecurity. It was called the next man up. And what that basically means is you go to the sideline holding your hip or whatever, and if you don’t come back soon enough, the next guy is in your spot.”

“This is survival out there, whether it’s amateur or pro. We started with that on the playground. A guy can’t play, the next man comes in, and he’s got the spot. Then the next game he’s starting, and you’ve got to earn your way back.”

Julius Erving does not criticize modern players out of bitterness. When he talks about load management, he frames it as a reflection of how different the league has become. In his era, sitting out healthy simply was not an option. Not because players were superhuman, but because their jobs were never fully secure.

For Erving, that mentality started long before the pros. On playgrounds, if you stepped off the court, someone else stepped in. If that replacement played well, you had to fight to get your spot back. There were no guaranteed roles. No protected stars. Just competition.

“This is survival out there, whether it’s amateur or pro.”

That survival instinct defined his career. Across 16 professional seasons in the ABA and NBA, Erving was the model of durability. His lowest total of games played in any season was 60, which came in his final year. Every other season of his career, he played 70-plus games.

He played 84 games four times in the ABA when that league had longer regular seasons. In the NBA, he logged 82 games twice and 81 games once. Missing time simply was not part of his routine.

“If you played 82 games, I wanted to play all 82,” Erving said. “It would take something dramatic to make me play less. You get a sprained ankle, you have to sit out a game or whatever, but then you come back. You come back real fast.”

That mindset was not blind toughness. It was tied to economics and opportunity. In Erving’s era, salaries were nowhere near today’s numbers. The gap between the first man in the lineup and the 12th man was not astronomical. If a starter sat, the backup had a real chance to take his role permanently.

In today’s NBA, franchises invest hundreds of millions into their stars. Rest is strategic, and lineups are protected. In Erving’s day, job security felt thinner. Sitting out voluntarily risked everything.

Even outside basketball, he carried that same discipline.

“Even back in elementary school, I never wanted to be late or absent,” he said. “That carried over into my basketball. I didn’t want to be late for practice, and I never wanted to be absent from a game.”

The results speak for themselves. Erving finished his career averaging 24.2 points, 8.5 rebounds, and 4.2 assists. He won one NBA title and two ABA championships. He captured one NBA MVP award, three ABA MVPs, two ABA Playoff MVPs, made 11 NBA All-Star teams, earned five All-NBA First Team selections, and built one of the most decorated resumes in basketball history.

For Dr. J, load management was not an option because availability was part of greatness. In his world, if you stepped aside, someone else might take everything you worked for.