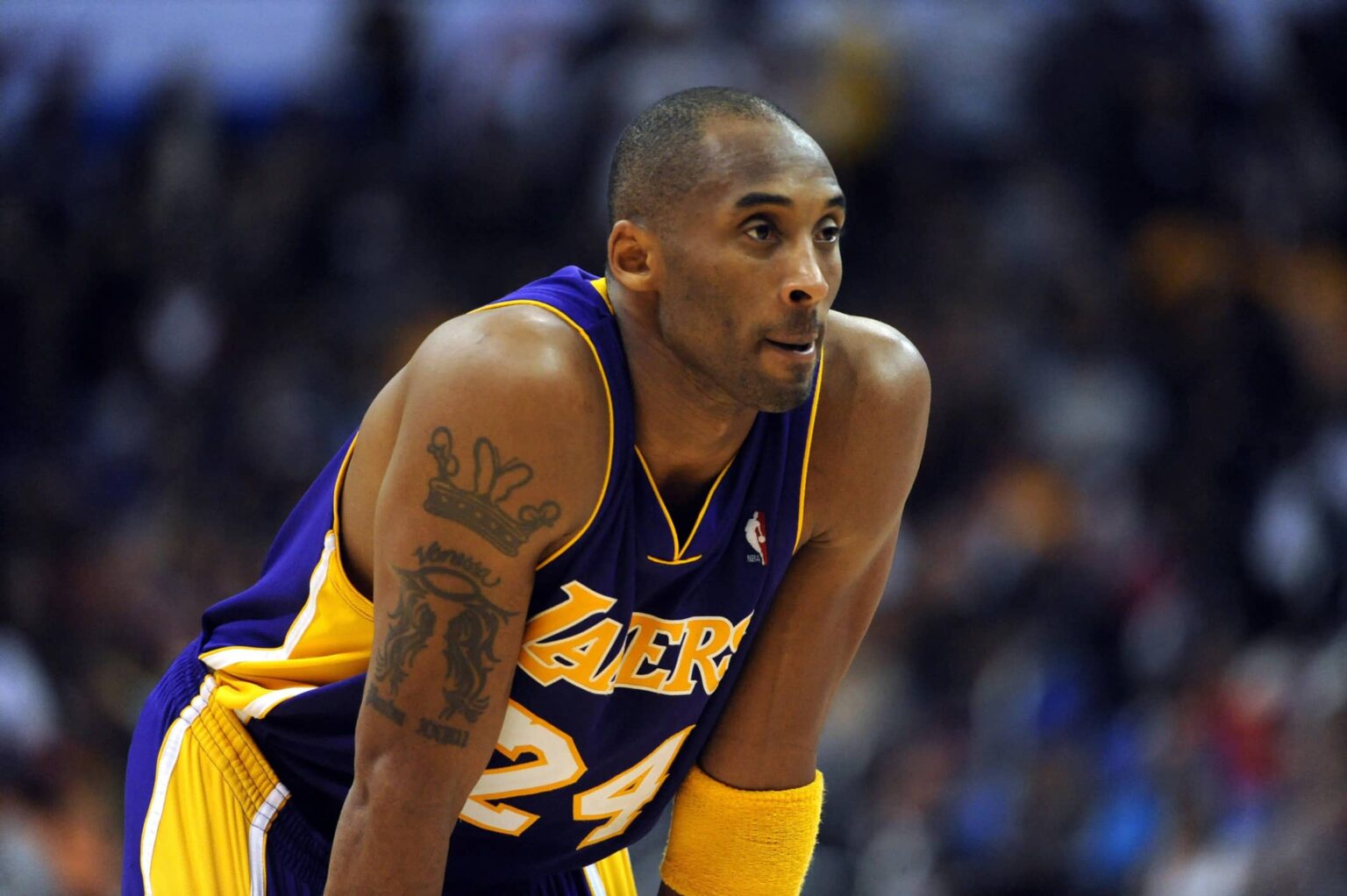

Stories about Kobe Bryant tend to orbit greatness, obsession, and edge. Occasionally, one cuts a little deeper and exposes how volatile that edge could be. Former Los Angeles Lakers forward Samaki Walker recently shared one of those stories, recounting a moment when Kobe crossed a line in the 2002-03 season and paid for it in a way that shaped both men.

Walker’s story came on Byron Scott’s Fast Break podcast and centered on something almost trivial by NBA standards.

“It was our second season and we were struggling that year. It’s funny because Kobe Bryant was methodical in everything that he did, right? He don’t just act out emotionally. A lot of times it’s thought out. And B Shaw had made me aware of some things that were going on, you know, in his life personally and things of that nature that was going on with Kobe when we were losing. There was several things that were going on at the time that he was holding in.”

“And you got to understand, he didn’t really have no vessel with all these things. You talking about an ultra competitive brother. Things that were going on in his personal life. And you know how he speaks about his dad and his parents and things of that nature. So you can understand how that may have impacted him not to have that connection.”

“We get to Cleveland right before we shooting at the end of practice. You know how we go, everybody’s shooting the long shot. One hundred dollars. So for one hundred dollars, you know, you get it, you make it, you get the pot. Long story short, Kobe end up winning the pot. And the rule is you got 48 hours to pay. Forty eight hours to pay and then you’re good. Everybody paid. I have never heard a story where somebody didn’t pay a hundred dollars.”

“So it was the next day. I think we got on the bus. For me, I didn’t have no cash on me at the time, but it was the very next day. It wasn’t even 48 hours yet. Kobe said, ‘Hey man, you got my money?’ I got my earphones on. We going to shootaround. He said, ‘Yo, you got my money?’ I said, ‘Man, I ain’t got my wallet with me. I’m in my practice gear and everything. I got you when we get back.'”

“So I put my headphones back on. Bow. Took off on me. Damn. Like what the f**k just happened? Because I totally wasn’t expecting that. I told the man I’m going to pay him his money. It wasn’t like I said I wasn’t going to pay you your money, bro.”

“By the time I could think about it, I went from zero to sixty. Now I’m thinking I’m going to kill this motherf**ker. I don’t give a f**k who he is or what. I’m going to kill him. Kobe sit way in the back of the bus, so he can’t go nowhere. Rick Fox, everybody jump up. I’m trying to get to the back of the bus. I remember throwing my phone, hit him with my phone and everything I had.

“They usher me off the bus. They locked me up in the back room. Wouldn’t let me come to practice or shootaround. I’m mad. I made up my mind. I already made bad decisions before. I’m about to make another one. I’m going to kill this dude. We get back to the bus. He done took off in a taxi. He gone. He got his bodyguards. They pre planned it. They ain’t getting back on the bus.”

“We go back to the hotel. My light blinking on my phone. It’s a message from him and the motherf**ker crying. Swear to God crying on my phone. Talking about he don’t know what was wrong, don’t know why he did what he did. Calling me a friend and everything. That made me understand there was some s**t going on bigger than basketball.”

Even then, Walker was not ready to let it go. He showed up early the next day, waiting. Ready. It took an intervention from Jerome, Shaquille O’Neal’s uncle, to pull him back from throwing his career away. Jerome told him plainly that the league would not side with him, no matter how wrong Kobe was. That reality check mattered.

When Kobe finally walked in, there was no bravado. No ego. Just a man who knew he had messed up. Walker confronted him directly, making it clear that putting hands on another man crossed every line that mattered. Basketball did not excuse that.

The surprising part is what came after. The two actually grew close. They talked. They understood each other. Years later, Kobe gave Walker a pair of his black Mambas from an All-Star Game, asking him to use them for his foundation. It was not a publicity move. Walker did not even realize what the shoes would one day represent.

This story casts no shadow on Kobe Bryant’s legacy. If anything, it makes it more human. It shows how his obsession with winning sometimes spilled over into something unhealthy, and how accountability and humility mattered just as much as competitiveness. Kobe was not perfect. He was intense, flawed, and driven to a fault. And sometimes, that meant learning the hard way where the line was.